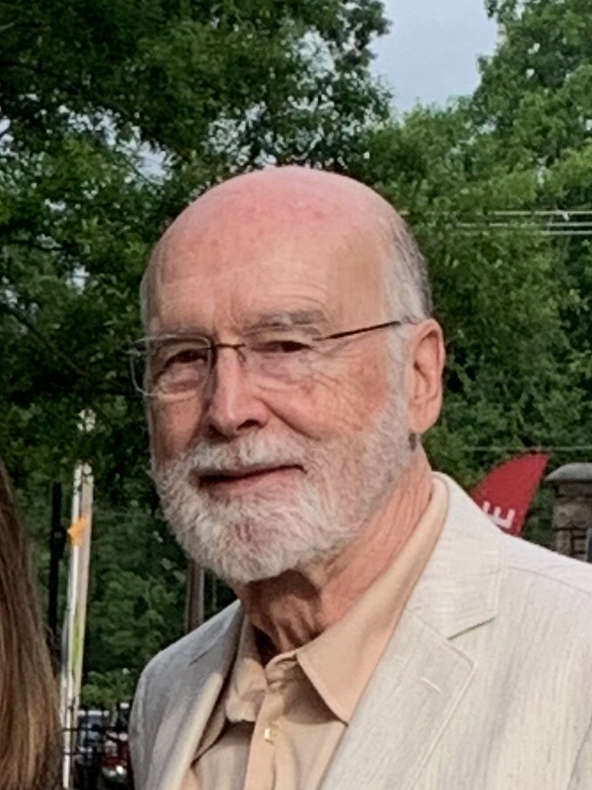

Former Faculty Member Spotlight-Dr. David Young

In the summer of 1972, I received my PhD degree in Physiology from Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. My dissertation research centered on short- term control of renin release and renal hemodynamics, subjects related to blood pressure regulation and hypertension. At that time blood pressure control and the causes of hypertension were poorly understood. Most people with elevated blood pressure were believed to be suffering from “essential hypertension”, a disease of unknown etiology.

During my final years in graduate school, I had read several papers by Arthur Guyton and his associates in Jackson, studies of long-term control of cardiac output and blood pressure regulation using quantitative analysis and computer simulation. What was most fascinating to me was the simple seven function negative feedback loop describing the basis of long-term control of cardiac output. I was amazed by the logical simplicity and power of this basic model of the circulation. I very much wanted to come to Jackson and work with Dr. Guyton and his group to analyze the causes of hypertension using quantitative analysis and mathematical simulation techniques being developed in Jackson.

Fortunately, Dr. Guyton offered me a post-doctoral fellowship to begin in August 1972. I replied to his offer with a letter of acceptance in which I mentioned I had developed something of a fascination for Mississippi from reading many of William Faulkner’s novels. He replied that modern Mississippi bore little resemblance to what Faulkner had written. Apparently, he had not heard Faulkner’s quote, "The past is never dead. It's not even past."

I came to Jackson in July to look for a house for my family. With the help of a real estate agent named Colonel Carleton Snodgrass, I found a suitable house that was probably more than I could afford and would certainly be a struggle to come up with a 20% down payment. The Colonel took me to Magnolia Bank and told them I was Dr. Young, “newly hired” by Dr. Guyton at the “Med Center” and he needs a mortgage on a nice little house. The banker promptly offered me a 95% mortgage with no credit check or any documentation of my pending employment or income. I quickly inferred that being associated with Dr. Guyton and the Med Center provided much more respect in Jackson than I expected as an about to graduate PhD.

My first days at the Department of Physiology and Biophysics were exciting, meeting students, fellows, faculty, technicians, secretaries, many speaking with heavy accents from foreign countries and northern origins, and of course most everyone else had a strong local Mississippi way of speaking. Meeting Dr. Guyton for the first time was memorable; he was very warm and friendly, relaxed and interested. From his reputation for brilliance and productivity, I was expecting a more intense, hyperactive departmental chairman who would have little interest in a new PhD entering his group that attracted attention for around the world of cardiovascular research. During my first six months in Jackson, I met with Dr. Guyton frequently to discuss hypertension and opportunities for me to begin my research studies.

In late September, a few weeks after entering the department, Sir John Ledingham from Oxford (England), an internationally renowned authority in the field of hypertension, came to Jackson to confer with Dr. Guyton and present a seminar to the department. One evening during his visit, Dr. Guyton hosted a dinner at his home on Meadow Road. Susan and I arrived at the Guytons’ home and were graciously welcomed by Ruth Guyton, Arthur’s wife, a beautiful, warm and gracious woman and wonderful hostess. It was a sunny evening with well-dressed guests filling the large home and the lawn flanked by flowers and pine trees. I don’t remember the food, but I can still see the beautiful early Autumn evening and how impressed I was by the guests and Dr. Guyton and Ruth Guyton. I had no doubt that I was very fortunate to be a member of such a group. (I can also clearly picture how the Guyton's and my contemporaries looked that bright, memorable evening 51 years ago!)

Several faculty members were unique in my experience, both before that initial meeting and ever since. Aubrey Taylor, Elvin Smith and Jack Crowell were truly “country people” in many respects, including chewing and spitting, telling tall tales about life in the South, close talking, and the use of “colorful” local slang expression, but they were also highly intelligent, serious scientists. They were all very interesting “characters” and each one was understanding and kind to me as I learned the ways of my new home in the South, which was very different from anything I had known growing up in the North and West.

At that time several popular hypotheses concerning the causes of hypertension included excessive activity of the renin-angiotensin system and aldosterone secretion, and excessive intake of dietary sodium. At that ancient time radioimmunoassays of hormones were in their infancy, and fortunately, Jackson had assays for both renin-angiotensin activity and aldosterone concentration. So, my first research in the department was a study of control of aldosterone secretion stimulated by changes in plasma sodium and potassium concentration (in the headless dog!), and then analysis of long-term changes in aldosterone concentration on blood pressure regulation. This latter study revealed that, contrary to the then current belief that potassium excretion was regulated by aldosterone, we found that in fact the regulation of potassium excretion was controlled by the interaction of several negative feedback control systems, only one of which was the aldosterone feedback; the more important factor regulating potassium excretion we found was the concentration of potassium in the plasma. We concluded that aldosterone’s main function was not to regulate sodium and potassium balance; other factors were more prominent factors controlling their excretion. Aldosterone’s function is to simultaneously match the rates of excretion of both sodium and potassium to widely disparate combinations of rates of intake of the two ions. The study of these interactions attracted my research attention for the next several decades and led to further interests in the relationship between potassium and vascular disease and hypertension.

At that time, an extensive literature suggested that there was a correlation between high levels of potassium intake and a degree of protection against cardiovascular disease. We began to investigate possible protective mechanism by which K could provide cardiovascular protection, first by analyzing the responses to changes in potassium concentration of human platelet aggregation stimulated ex vivo by ADP or epinephrine. We found that sensitivity to ADP but not epinephrine was reduced by acute physiologic elevation of potassium concentration ex vivo, and in subjects whose K concentration was elevated over a five-day period.

We also studied the effect of acute and chronic K elevation in a dog model of coronary artery thrombosis in response to endothelial damage (Folts model). In anesthetized dogs, acutely raising K concentration by iv infusion had an inhibitory effect on the rate of thrombus formation. And in dogs fed a diet with elevated K levels, the long-term elevated plasma K concentration had an inhibitory effect on the formation of thrombi.

The vascular protection afforded by K supported by population-based studies suggested that K may act on the mechanisms responsible for atherosclerotic vascular lesions. To investigate the possible mechanisms for the protective effect, we first studied free radical formation ex vivo in human monocytes and observed a significant reduction in rate of free radical formation in response to elevation of medium K within the physiologic range. Next, we analyzed the effect of physiologic increases in K concentration on rate of migration of vascular smooth muscle cells through agar over a period of days. Migration of smooth muscle cells from the muscularis to the intima is a critical factor in arterial lesion formation. The rate of migration was significantly reduced in media with elevated K concentration.

The responses to elevation of K in several chronic models of arterial vascular lesion formation were studied in our lab, including coronary arteriolar lesion formation in the fat-fed rabbit, in the rat model of lesion formation in response to endothelial damage due to balloon injury in the carotid artery, and in the pig in a similar model of endothelial damage in the coronary left anterior descending artery. In all three, elevation of K intake over periods of several weeks was associated with significant reductions in measures of lesion formation.

We believed changes in K intake and plasma concentration could affect cardiac contractility. Experiments were designed to analyze contractility first in two groups of anesthetized dogs with extensively instrumented left ventricles, one group fed a diet with reduced levels of K and another group fed a high K diet. The dogs with higher K intake had significantly great measures of contractility and power generation that the dogs in the reduced K diet group.

Subsequently, we extended the cardiac investigations to human studies in volunteers, first after a week of K supplementation, then in the same individuals after a period of K depletion. Cardiac function was analyzed using Doppler techniques during a dopamine stress test protocol. K supplementation resulted in elevated measurements of cardiac contractile and in indices of relaxation.

My last year as a faculty member I was invited to write a book concerning my study of potassium’s cardiovascular effects. I wrote the book, Role of Potassium in Preventive Cardiovascular Medicine, that included many of the findings of our potassium studies. It was published by Kluwer Academic Publishers a few weeks before I retired in 2001. Since then I wrote two other books for use in graduate study, Control of Cardiac Output (2010) and Control of Potassium (2013), both published by Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences.

After retirement my wife, Susan, and I divided our time between our homes in Ridgeland and Basalt, Colorado. Initially, we spent 4 to 5 months each year in the mountains and traveling to visit our children in Germantown TN, Washington DC and Seattle WA, and parents in Port Charlotte FL, the rest of the year in Ridgeland. In 2013 we moved to Germantown to be close to our son and his family. I read extensively, making up for lost time when I was too busy to read for pleasure: history, biographies, a novel or two each year, and daily, the New York Times and Washington Post. My serious avocations include skiing and trout fishing in Colorado, and duck hunting near our cabin in the Mississippi Delta. Susan and I have enjoyed traveling extensively, notably to the Greek Isles, Italy and Sicily, Scotland, and to Switzerland visiting Jean Pierre (former post doc and visiting faculty) and Michelle Montani, and to southern Africa where we reunited with Roy Bengis (a former student and good friend) whom I had not seen for about 30 years.

Recently, all 10 members of our family met at a resort in eastern Tennessee, arriving from near and far for a rare four-day family reunion, probably the best four days grandparents could ever expect!